Stitched together.

Artist Susan O’Doherty uses recycled materials and found objects to create artworks that speak particularly to the challenges facing women, past and present. For the exhibition A Conspicuous Object - The Maitland Hospital she turned her attention to the women who have worked and work in the Maitland Hospital.

She created twelve ‘textile sculptural heads’.

Susan O’Doherty’s textile sculptures installed in the exhibition, A Conspicuous Object - The Maitland Hospital, October 2021.

(Clare Hodgins)

“My focus is on the dedicated women whose roles are central to the history of the Maitland Hospital. My textile sculptural heads depict doctors, nurses, kitchen staff, volunteers, laundresses and receptionists from the first woman in charge, Matron Elizabeth Morrow in the 1870s, to a contemporary emergency physician. Relating to the current Covid pandemic, one of the sculptures is in memory of Mary (Mollie) Carr, a 23-year-old trainee nurse who died in 1919 within a week of becoming ill with the ‘Spanish flu’.

Though each is a solitary figure, these armless three-dimensional textile sculptures bear a relationship with each other in the manner of a collective hospital team. Some are literal and others more abstract. Textiles and found objects dictate their professions and duties within the hospital. A sense of memory, activities and events from the past are made present through stitching together fragments of uniforms, scrubs, clothing, bedsheets, curtains, towels, bandages, tea towels, scarves, lace, ribbons and gloves. I can visualise these women walking through the halls and wards of the hospital.”

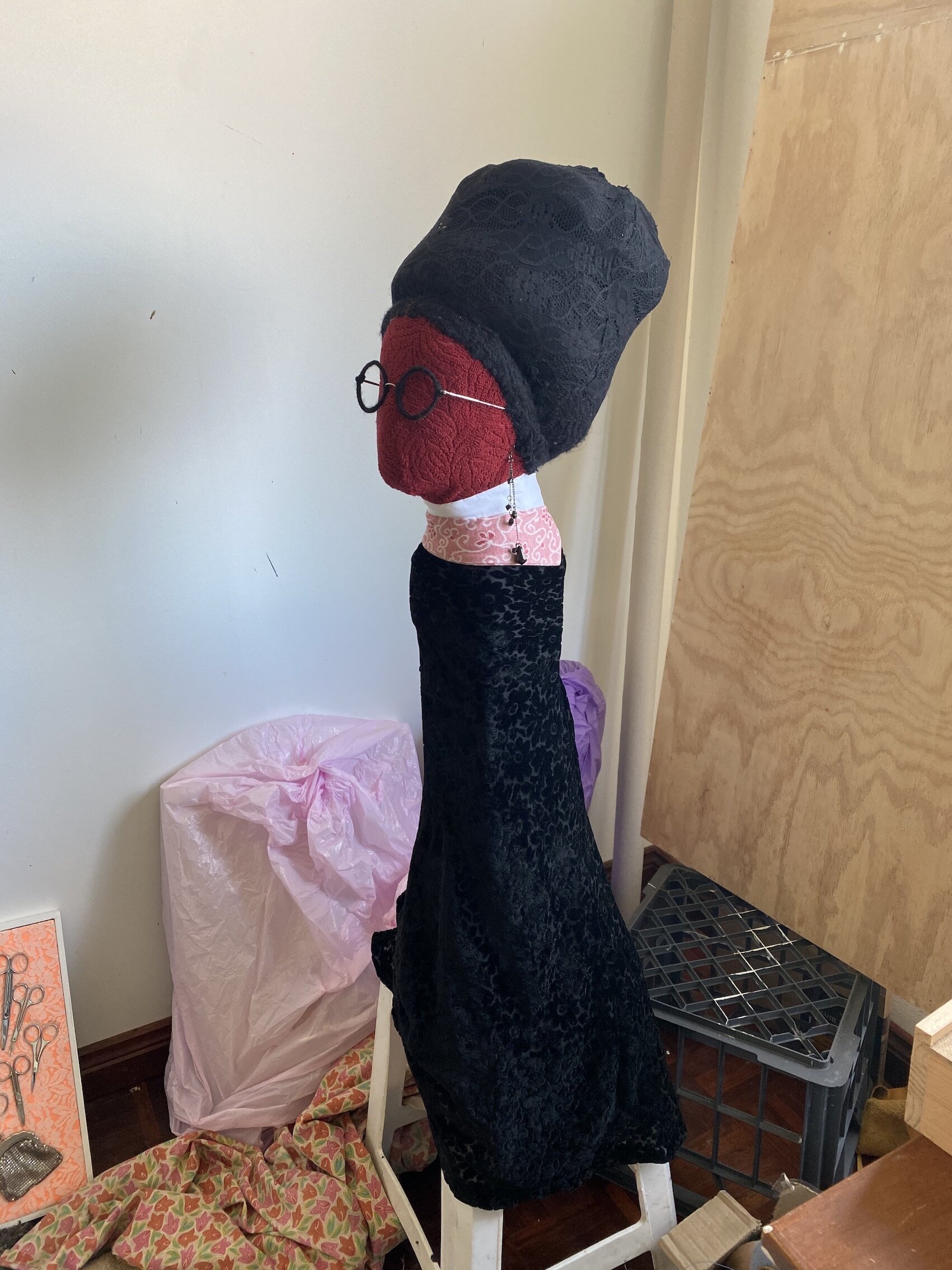

First matron - Elizabeth Morrow

85 x 35 x 20 cm

Elizabeth Morrow (1842-1886) was the hospital’s first trained nurse and matron. Her story resonates with the challenges of women being given management responsibilities in a male dominated world.

I used a black and white photograph of an 1880s portrait of Elizabeth Morrow in her nurse’s uniform to try to capture her likeness. The portrait presents a stoic, determined and strong woman staring directly ahead.

I’ve dressed her in black, capturing the era of the day, using lace and chiffon, and I have kept her simple and unadorned apart from the large green brooch centred below her collar. Her hair is covered with black lace, bunched on her head with a white lace cap. I wanted her to be a commanding figure.

Susan O’Doherty created a second sculpture of Deborah Morrow as the centrepiece of a display in the new Maitland Hospital about the role of nursing.

Charity worker - Elizabeth Heyes

87 x 35 x 30 cm

Elizabeth Heyes (1863-1940) is representative of the many women who, over the history of the hospital, have volunteered their time and resources to assist the institution. Her story highlights both her assistance to the hospital and her wider community activities.

As a reference to make my sculpture I used a 1940 obituary head and shoulders photograph from the Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate newspaper. From that, and earlier photographs, Heyes appeared as a slightly eccentric woman with a kind but determined demeanour.

I’ve created her with materials of the day, dressed in a long flowing black lace gown with an art nouveau patterned pink neck with white collar, a deep maroon chenille face, a mass of dark hair bunched on her head, horn-rimmed glasses, and long dangling black earrings.

The short life of Nurse Mary (Mollie) Carr

85 x 20 x 25

Mollie Carr (1896-1919) was in the fourth year of her nurse’s training at the Maitland Hospital when the ‘Spanish Flu’ arrived at the end of the First World War. The first diagnosis of influenza patients was in April 1919 and over the next 8 months there was a growing number of influenza patients. Deaths from the disease peaked in June and July and Mollie Carr, who had joined other Maitland Hospital nurses working the wards of suffering patients, contracted the disease and passed away within a week.

I chose Mollie Carr for her commitment as a young woman and as a figurehead to remember all Australian nurses who should be recognised for their service around the time of the First World War. As well, 100 years on since the Spanish Flu, Covid19 arrived in Australia. This makes Mollie’s story even more poignant and relevant.

She is dressed in white. I used a stretched nylon material to sew together her flowing dress, and white cotton shirts for her blouse and nurse’s cap. A lace mask representing the butter cloth masks used at the time covers a deep maroon chenille face.

Maternity nurse

90 x 55 x 25 cm

Until early in the twentieth century, women mostly gave birth at home or in small nursing homes. Hospitals then slowly took over. Maternity wards were established and specialist midwife training became available. Maitland Hospital conformed to this pattern and, since the early 1900s, has cared for women and babies who live in the Maitland, Cessnock, Kurri Kurri and Dungog areas, and other women and babies from across the Hunter New England Region.

Maternity Nurse pays tribute to the women involved. Raised on a textile mount, a white cane pram represents the maternity wards, nurses and women who have given birth at Maitland Hospital over time. The late 19th century castor oil bottles and mid 20th century ½ pint milk bottles provide a link across the decades. The bottles also symbolise motherhood, the care given in the journey from pregnancy to birth, and the postnatal support mothers receive from nurses and midwives at the hospital.

Graduation day

123 x 30 x 30 cm

Maitland became a prominent training hospital for nurses from 1902 to 1987. Graduation photographs of nurses at different times illustrate this.

My graduation nurse wears a blue buttoned up uniform under a headdress of gloves. Sourced through boxes of vintage and contemporary gloves, I stitched together layers of cascading gloves to represent the nurses who graduated at Maitland Hospital over the decades. On receiving their diploma at the graduation ceremony, the new nurses would present in their ironed uniforms, starched caps and white gloves. The white gloves were part of the uniform. They also represent commitment, service and hygiene.

A beacon of light night nurse

125 x 20 x 20 cm

Night nurse illustrates changes brought about in the early twentieth century. The arrival of electricity in Maitland in 1922, for example, would have brought vast changes to the workings of the hospital.

I constructed the Night nurse to be tall, upright, resilient and efficient, having a strong presence. She wears a full-length blue uniform buttoned up to her neck, a watch and an early 20th century cap with a light globe on her head. The globe represents both a major technological advancement and her presence, service, comfort and a new era.

In the kitchen

90 x 30 x 30

Looking through newspaper articles and photographs in the Maitland Hospital Collection, I was taken by pictures of women who had given long service as cooks and waitresses for much of their working life at Maitland Hospital. Kitchen work in a hospital is high pressure with tight schedules and heavy workloads.

I visited some of the staff at the hospital kitchen in 2020, where it was a hive of activity preparing food for the wards. The women were friendly with a spirit of camaraderie and good humour. The head cook kindly supplied me with a cook’s shirt for my sculpture In the Kitchen. I used this soft green striped buttoned shirt as the uniform, connecting the head, plaster hand (with nail polish to underline the female workforce) and stove element as one entity to emphasise the multiple tasks within the kitchen at any one time.

1970s’ receptionist

100 x 20 x 25 cm

The reception and switchboard operator is the first person you see or talk to at a hospital. Almost always female, she controls the ebb and flow of communication and is a link to all services within the hospital, receiving and transferring calls to all departments. During the peak hours of the morning at Maitland she handles hundreds of calls every hour. Other duties may include clerical and secretarial.

My 1970s’ receptionist has three black velvet covered phones concertinaed on her head referring to the relentless volume of calls that would come in. As receptionists were not required to wear a uniform, I dressed her in classic woollen black and white houndstooth to complement the black phones, and attached the cord of the phone to her ear.

Pink Lady

90 x 28 x 25

The ‘Pink Ladies’ began working in The Maitland Hospital in the early 1970s and, in around 2010, morphed into the Maitland Hospital Volunteers. They are part of a long line of very dedicated women who began volunteering at the hospital from the time of its establishment. Elizabeth Heyes was a notable example. She is the focus of my Charity Worker sculpture.

Pink Lady represents all the women who have continued to put their time and energies into a variety of tasks to provide comfort and services for patients.

Today, the hospital volunteers wear pink and white candy striped shirts. They are bright and cheerful. Supplied with one of these shirts, I dressed my pink lady in various shades of pink. She has a soft cotton face with white spots, maroon woollen balls with a plaster hand with pink nail polish like a fascinator on top of her head - a symbol of giving, helping and supporting.

Psych Volunteer

80 x 30 x 25 cm

Psych volunteers have a specialised role. They work particularly with patients needing emotional and psychological support.

The psych volunteers’ smocks are a sunny bright yellow, approachable and friendly. The colour also clearly distinguishes the volunteer from medical and nursing staff.

My Psych Volunteer is dressed in her yellow shirt with a maroon floral smock to match her face and neck. Mustard yellow mohair wool for hair with a plaster hand with nail polish like a hat on top of her head - again to denote volunteer service and a helping hand.

1970s laundress

70 x 38 x 25 cm

Throughout its history, Maitland Hospital has been serviced by women who did laundry work. In the early years there was a pattern of engaging a husband and wife – the husband worked as the attendant and wardsman, the wife did washing and cleaning.

Being a laundress in the hospital in Victorian times was labour intensive, hard back breaking work . The bedsheets, hospital gowns, and personal clothing had to be soaked, rinsed and swirled in large tubs of boiling water. Scorching and scalding injuries were common. Laundry was scrubbed over a washboard, starched, blued, bleached, wrung, then hung out to dry. Final tasks were hours of laborious ironing and folding. The irons were very heavy and took a lot of time to heat manually.

From the late nineteenth century the first washing machines were being tested but it wasn’t until the twentieth century that machines became ubiquitous, irons lighter and electric, and the load became lighter.

I chose to focus my work on a more contemporary 1970s laundress whilst referencing the past. Her clothing is two tone with a soft grey woollen base with velvet buttons and a black velvet wringer handle which extends over the top of her head as if resting on an iron stand. The white towelling face represents the bleaching and starching along with an incredible range of other treatments in the effort to erase all stains. Her flesh and the metal of the iron and handle act as one whole encapsulating the person, the act and the mechanism as one function.

Emergency physician

112 x 26 x 30 cm

Until well into the twentieth century, the doctors at Maitland Hospital were male. The later twentieth century witnessed changes to hospital professions as they are known today. Rigid discipline was relaxed; starched uniforms were replaced by more practical and comfortable uniforms and women filled all medical and allied health roles including doctors, occupational therapists, optometrists, osteopaths, pathologists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, podiatrists, psychologists, radiologists, social workers and speech pathologists.

Emergency physician was the last sculpture I completed. It is of a contemporary doctor at the hospital in 2021 during the Covid Pandemic. I was supplied with photographs of the emergency doctors at work and with an emergency physician’s scrubs which I cut and sewed onto the long narrow figure of the sculpture with her job title embossed. Her red woollen face is stitched together like a patchwork referring to a surgeon’s work. She wears a white mask as a reference to hospital practice and the current Covid pandemic - a century on since Nurse Mary Mollie Carr passed away from the Spanish flu in 1919 tending to sick patients at the hospital.

Making the sculptures

My mother was an obsessive sewer and mender. As I grew up she would constantly be laying out and cutting patterns on the lounge room floor, darning socks, fixing things and sitting at the sewing machine. She made pyjamas, shirts, dresses, shorts, pants, almost all our clothing. It was partly the frugality of the times but also probably as a creative outlet to escape the mundanity of other housework and domestic duties. As a teenager my sisters and I would go with her to rummage through op shops looking for clothes, fabrics, trinkets and oddities relating to past decades and generations. Her resourcefulness and creativity was contagious and I think has fed into my making and sewing these textile sculptures.

My process of making the sculptures involved thinking about the symbolism of different materials and forms as well as sorting out the practicalities of stitching everything together. Considerations included the following.

New and recycled materials

I used new and recycled materials for the heads and clothing. Stitching together an array of materials, colours and textures references the ways in which sewing and mending clothes relates to traditional women’s work - craft, needle and thread, domesticity and femininity.

Clothing and uniforms

The clothing and uniforms we wear relate to place and identity. I used real uniforms (scrubs and shirts) provided by Maitland Hospital staff and reimagined others by incorporating found objects to represent specific tasks and roles in the hospital.

Colours, textures and objects

I sourced fabrics and items from op shops: bed sheets, pillow cases, blankets, towels, linen, curtains, nighties, stockings, gloves, hats, tea towels. I used these materials to reference repetitious tasks that are done daily, weekly, monthly, yearly: washing and rewashing, making and remaking beds, wrapping and rewrapping bandages. And, in terms of colour, historically nurses were dressed in stiff white and blue uniforms that were reflective of the white surrounds of the hospital wards, walls, floors. Colours that evoke orderliness, hygiene and efficiency.

For the twentieth century sculptures, the fabrics, colours and textures are more contemporary. They are brighter and lighter, and incorporate floral and geometric patterns. I used chiffon, crepe, linen, satin, rayon, nylon, hessian. To find the materials I rummaged through boxes of offcuts and of children’s and women’s clothing: jumpers, dresses, shirts and shorts, cut fabrics and wool of all colours and textures, velvets, cottons, flannel, silk ribbons, handkerchiefs, stockings, scarves, bras, petticoats, hats, beanies, ties and gloves.

Where applicable, I used brooches, earrings and spectacles for distinguishing features. In the case of Night Nurse, buttons and a watch.

Bases and heads

The wooden bases and latex and foam heads are under-wrapped in malleable layers with a soft underfelt of various stretchy materials to build up the heads to a fuller form. The heads are then completed with outer layers of carefully selected fabrics cut and stitched over the underfelt. All heads are featureless and devoid of expression. They are stylised to represent the many workers of diverse backgrounds who have passed through the hospital over the decades. I avoided using obvious flesh tones in the faces, instead blending different tactile textures and various shades of deep reds, soft pinks and maroons. Perhaps I chose these colours to represent blood or life.

Hair

For the hair, I cut latex into long narrow strips, stitched material around them, then coiled and layered the strips to achieve shape and bulk. To finish I covered the hair with lace, felt and blanket materials. With the figures from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (eg. Matron Elizabeth Morrow and charity worker Elizabeth Heyes) I favoured black lace to denote the era and hairstyles of the time where the hair is stacked or coifed. I used various wools for the sculptures representing the more contemporary twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Drawing the sculptures

After completing the sculptures, I decided to do drawings of most of them. This connected to the long-standing tradition in the hospital of commissioning portraits of people associated with the institution.

Each drawing:

pencil, oil crayon and acrylic on paper

53 x 36 cm

Inspired to create your own sculptures

Inspired by Susan O’Doherty’s textile sculptures, artist education Liss Finney provides ideas for children to create their own soft sculptures at home.

Create a soft sculpture workshop.

Produced by Newy Digital for Maitland Regional Art Gallery, December 2021.

First posted: 16 October 2021

Updated: 12 April 2022