Horse-drawn ambulances.

In 1890 Thomas Judge successfully tendered to house and manage the ambulance service for Maitland Hospital. His descendant, Denise Porter, has generously shared her research about him and the service he provided.

Background

Thomas Judge was born at Morpeth in 1842 and died at Maitland in 1922. As a young man he went droving and, on returning home, he was employed as a carter for the fellmongering business he had worked for before leaving Maitland. He then established his own livery and van and parcel delivery service which he managed until his death.

In 1866 he married Sarah Annie Simpson who was born at West Maitland in 1847. They first lived in Durham (now Denman) Street, Maitland.

The NSW Births, Deaths and Marriages index indicates that eleven children were born to the Judges between 1867 and 1892. Four died in infancy.

Central Horse and Carriage Bazaar

In 1884 Judge purchased the Tallyho Livery Stables in High Street, Maitland. He renamed the business the Central Horse and Carriage Bazaar and advertised that he intended ‘to carry on the same as heretofore and also my van and parcel delivery’.

Maitland Mercury, 29 June 1884, p 3.

Advertisement announcing the opening of Central Horse and Carriage Bazaar.

View of High St, West Maitland, 1867.

The photograph was published in the Maitland Daily Mercury, 1 November 1935, with the caption:

‘The cottage in the foreground was the building occupied by Mr. Thos. Judge, and was situated on the site of the present building of Dimmock’s Ltd. The old bus shown was owned by Mick Hamer, and was called “The Shamrock”. The Methodist church can be seen in the background.’

The photo clearly predates Judge’s occupation of the site. Peter Smith observes that a livery business was established on the site by William Taylor in the 1860s. George Miller was a subsequent owner and Thomas Judge acquired the property from Miller in 1884. The livery stables were at the back of the cottage.

Judge’s business occupied the High Street premises for the next three decades. In 1911 he moved to the corner of Michael and Bourke Streets (near where K-mart carpark is today). He purchased the property from David Cohen and Company Limited. It was described as ‘a weatherboard cottage of five rooms with slate roof, outbuildings etc’ and Judge aimed ‘to erect stables and buggy sheds on the vacant land for the conduct of his business’.

Maitland Hospital ambulance service

In 1890, Judge successfully tendered to house, operate and service the ambulance for Maitland Hospital and, apart from a brief period in the early twentieth century when the contract was awarded to Thomas Bellamy (who purchased Judge’s High Street premises in 1911), Judge’s contract was renewed until his death in 1922.

Newspaper reports indicate the nature of the service he provided and the nature of the ambulance service at the time.

Maitland Hospital sub-contracted its ambulance service. It seems the hospital owned the hospital wagon. The sub-contractor housed the wagon, provided the horses and cared for them, and responded to calls for ambulance assistance. The hospital charged fees for the use of the ambulance, except presumably for those who could not afford to pay. The fees, it was hoped, would cover the cost of the sub-contract.

Judge provided a satisfactory service. In 1897, for example, he was praised for the speed with which he drove a doctor (Bowker) to attend to a serious accident at the East Greta Colliery:

[Judge’s] smart performance in getting out is worthy of the highest commendation for, from the time he heard of the accident, until landing the doctor at the pit top, only twenty minutes elapsed.

One of the challenges was communication. Sometimes Judge was called on directly; at other times the hospital was approached. The practice was that, when a call went directly to Judge, he was supposed to go to the hospital, get approval and collect a nurse. This, at times, proved cumbersome and inefficient.

As early as 1900 there was discussion about organising a telephone connection between the hospital and Judge’s residence (‘who has charge of the hospital wagon’) to improve the hospital’s ability to respond to calls for assistance using the hospital ambulance. The following year Judge pointed out that ‘the only thing that annoyed’ him was the need to get permission from the medical staff or matron for him to respond to calls that were made directly to him. This provoked a lengthy discussion in the Hospital Committee. The concern was to ensure that a nurse travelled with the ambulance to provide medical assistance. Attention returned to connecting the phones between the hospital and the ambulance provider.

Judge, as ambulance sub-contractor, also played his part in selecting and caring for the ambulance vehicles. In early 1908 he was one of two men sent to Sydney by the hospital committee to look at ambulances being built there. A couple – including the one used in Newcastle - were considered too heavy for country roads. One, by a Mr Olding, seemed suitable. The hospital committee sought advice about whether to order one from Sydney or get one locally. The decision was to order one locally. The firm of Hammond and Moore were engaged to build the vehicle. In November 1908 the Maitland Mercury provided a lengthy description in praise of this ‘up-to-date’ vehicle ‘built on the lines of the Coast Hospital ambulances, Sydney’.

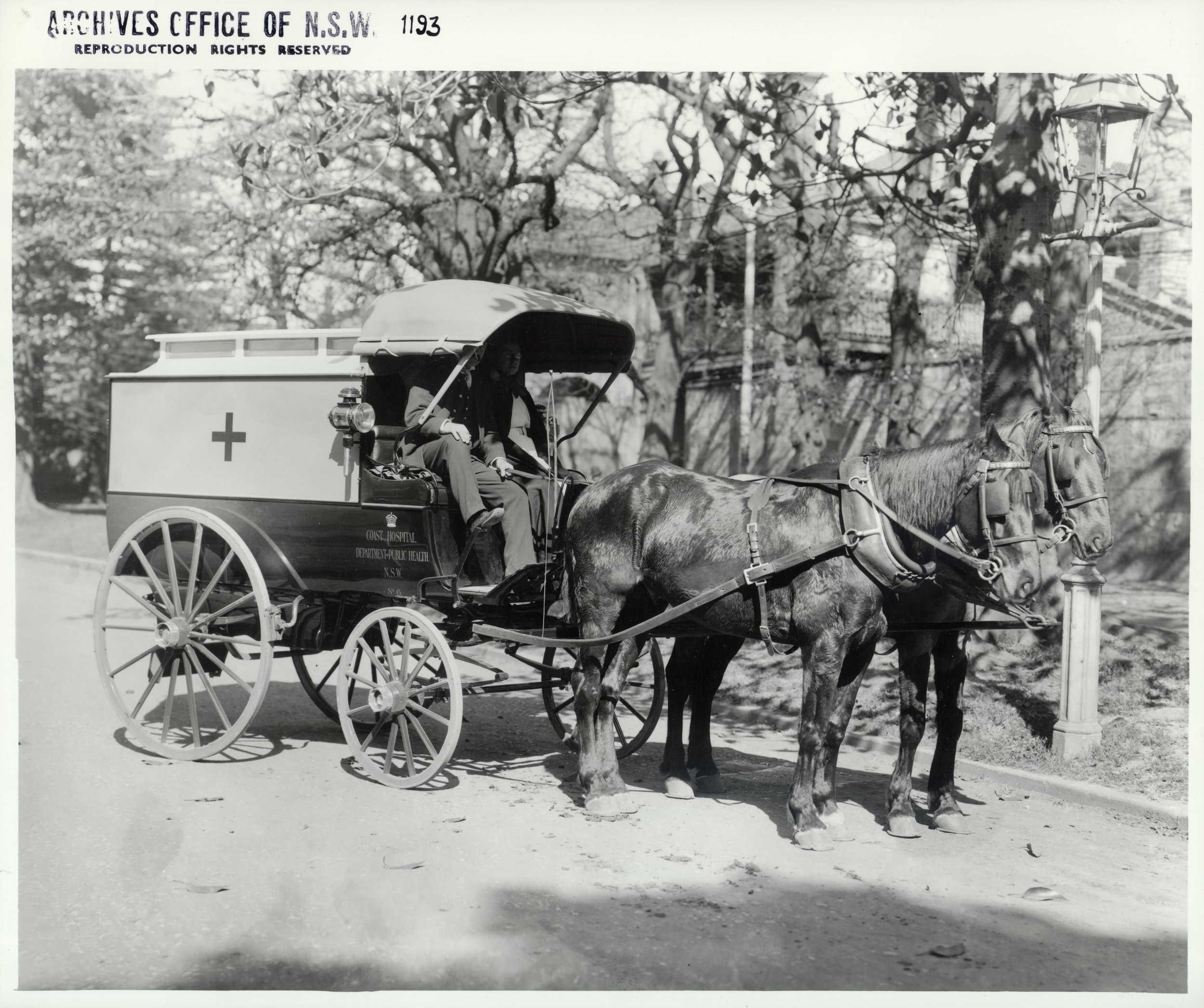

Department of Public Health, Coast Hospital horse drawn ambulance.

To date, no photographs have been located of Maitland’s horse-drawn ambulances. This photograph of a Coast Hospital ambulance - used as the model for the new 1908 Maitland ambulance - provides some idea of what the new ambulance looked like.

The Maitland Mercury article lists the different timbers used in the vehicle - English oak, cedar, kauri pine - and describes in detail its features. These included:

The top of the ambulance … built on the same style as the saloon railway carriages, having a lantern roof, with panels of glass running along the sides, the centre panels working on pivots, so that they may be used for purposes of ventilation if required.

There is mention of the two doors at the back of the vehicle, each with ventilation; a ‘caned stretcher’ with webbing and ‘rubber-tyred wheels, which run in grooves; a seat for the nurse; a kerosene lamp to provide light at night; folding steps at back; and room for two patients.

Unlike the old ambulance, the front of the vehicle is protected by a large duck-covered hood, and there is room for the driver and two nurses comfortably.

The article also provides details of the construction and features of the carriage itself including, for example, the dimensions of the wheels. The article ends with a description of the colour scheme and cost:

The new ambulance was clearly in use over the next few years. By 1915 Judge recommended to the hospital committee that ‘the improved hospital wagon required attention’:

… [he] was of the opinion that the body of the vehicle should be painted and varnished and thoroughly renovated, and it was also a question of whether it would be advisable to have the rubber tyres attended to.

Judge was asked to obtain prices for the work and, if it was not too costly, the hospital committee was empowered to approve.

It is also apparent that the ambulance service, and Judge as the provider, had to adapt to changing circumstances. During the 1919 Spanish flu pandemic the hospital committee decided to convert the single-horse ambulance to a two horse ambulance and provided Judge with 2 pounds per week to hire the required two horses. In 1921, the hospital committee decided to change an existing practice to not send out the ambulance at night. It resolved that ‘in urgent cases the ambulance be sent out at any hour of the night, and that two nurses or a nurse and a lady friend, accompany the ambulance’.

Judge’s contract for the ambulance service was renewed in 1922. He died that year. The era of horse-drawn ambulances was ending. In the early 1920s there was successful lobbying for a community managed and motorised ambulance service in Maitland. Tom Healy’s grandfather, Hugh Healy, played a significant role.

References

Maitland Mercury, 29 June 1894, 16 November 1895, 13 January 1897, 7 November 1900, 30 July 1901, 27 February 1902, 27 February 1904, 7 March 1908, 5 March 1910, 22 July 1915, 16 March 1916, 28 June 1919, 17 November 1921, 12 January 1922.

Newcastle Morning Herald, 29 November 1922.