He was carefully attended.

Glimpses of changing surgery practices across the 19th century.

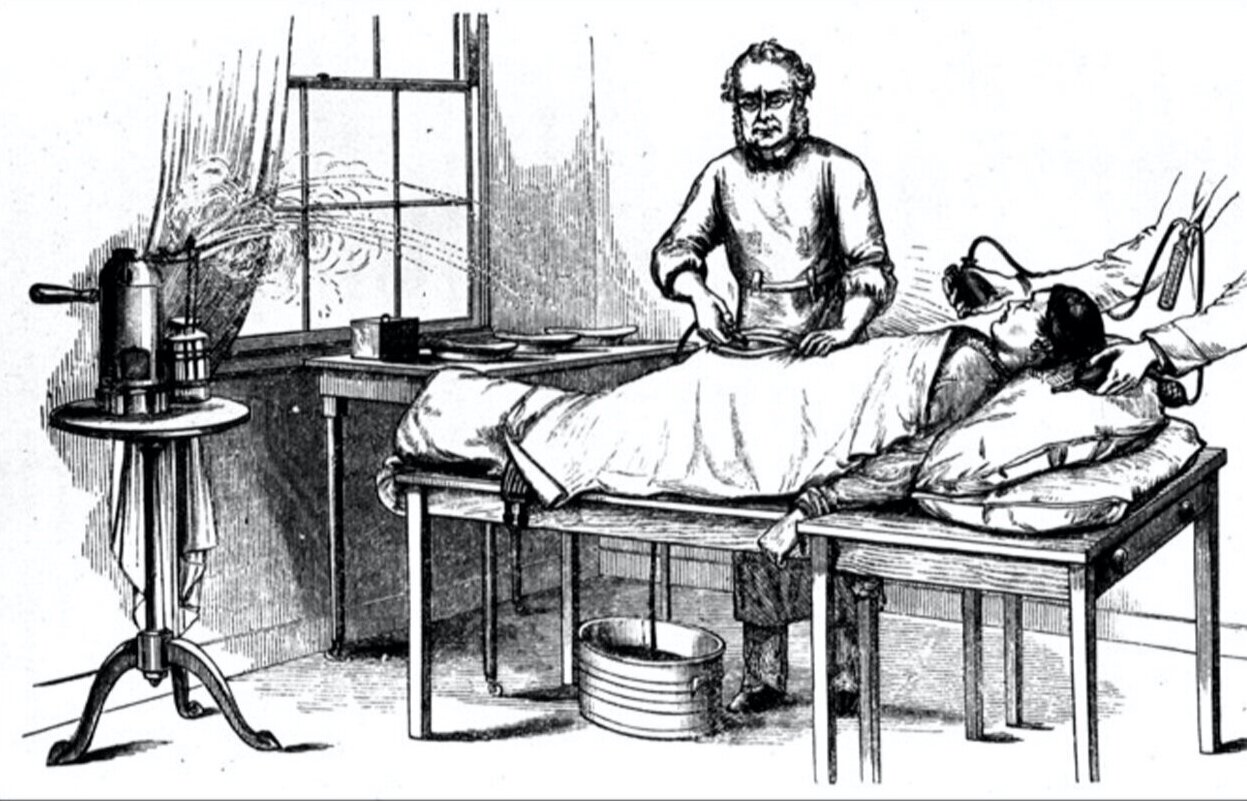

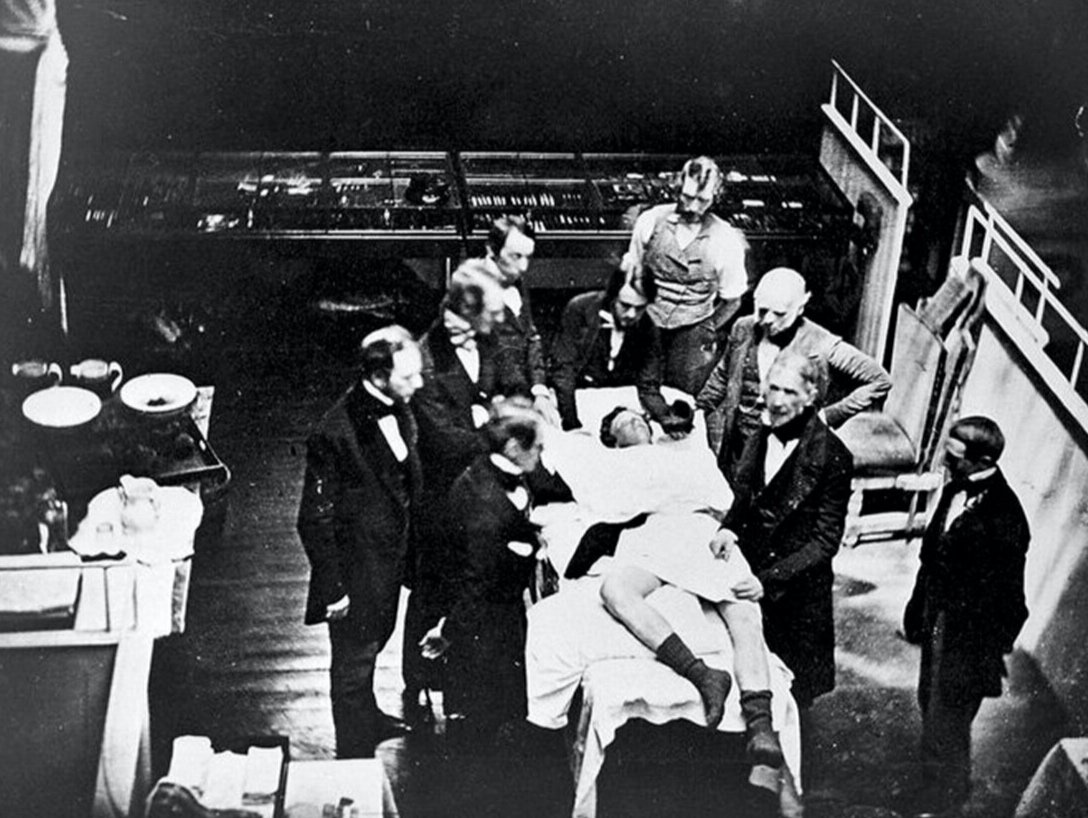

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, hospital care in the western tradition generally involved bed rest, blood-letting, the care of wounds and the administering of medicines. Operations were a last resort and, when needed, they were conducted without anaesthetics, with limited understanding of the importance of a sterile environment, and with what today appear as rudimentary and often savage surgical instruments.

Some change was brought about through the introduction of the use of ether and then chloroform in the late 1840s and, from the 1880s, with the opening of the first aseptic operating theatre. By the end of the century, an increasing number and variety of operations and other forms of medical treatment were performed in hospitals.

The Maitland Hospital reflects this pattern.

During the last quarter of 1844, for example, the list of diseases of the 21 patients admitted to what was then the Maitland Benevolent Asylum consisted of:

1 fracture of forearm, 3 ulcers of leg, 1 erysipelas, 2 paralysis, 1 hydrocele, 1 ophthalmia, 2 rheumatism, 1 consumption, 1 disease of heart, 1 hip disease, 3 seq. syphil., 1 old age (82), 1 testitis, 1 carbuncle, 1 name not entered.

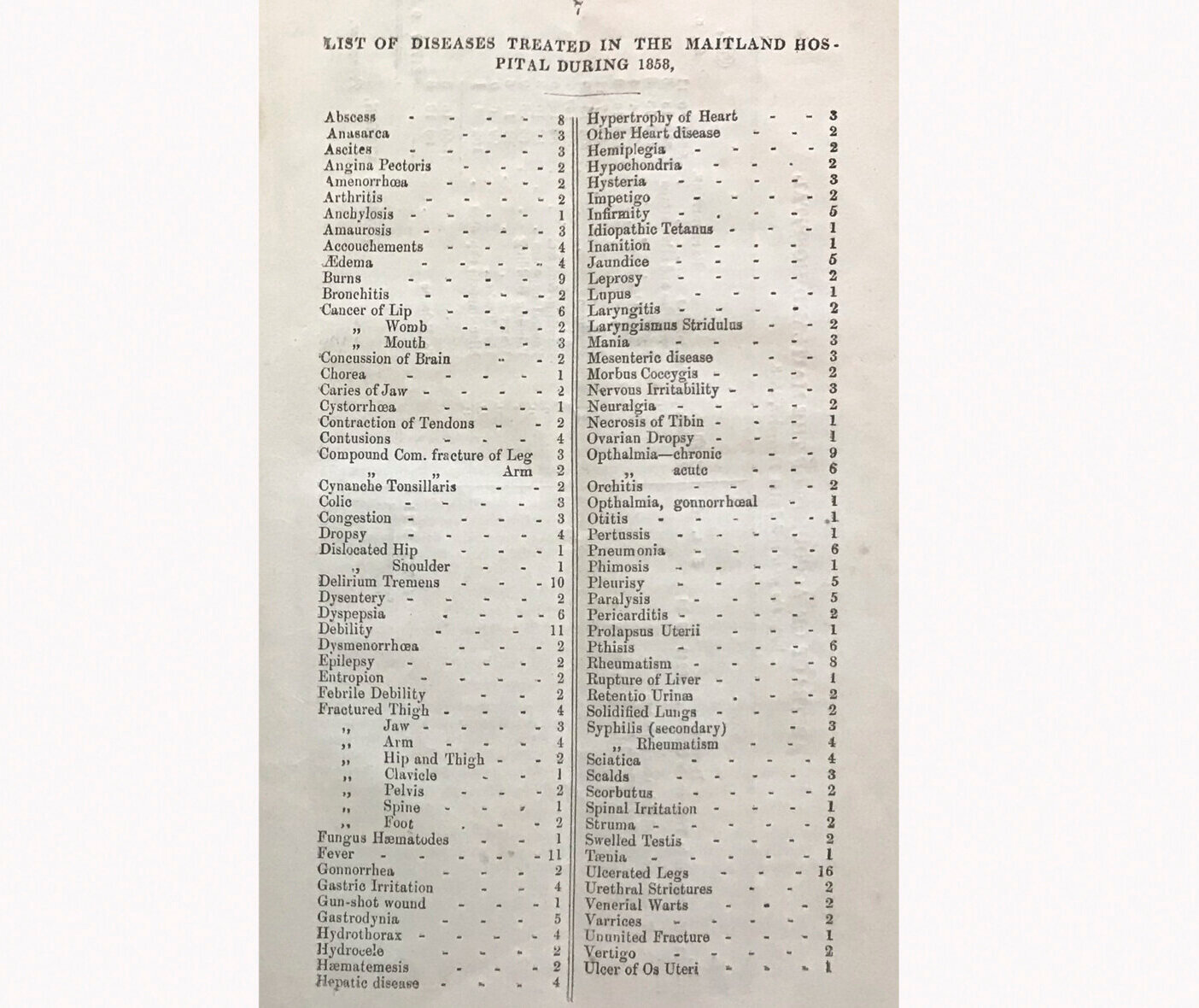

In 1858 they included a variety of fractures, burns, scalds, fevers, infections, women’s health issues, eye diseases, sexually transmitted illnesses, urinary tract problems and cancers.

List of diseases treated in The Maitland Hospital during 1858, The Maitland Hospital Annual Report, 1858,

(Newcastle Region Library)

During these earlier decades of the century, fractures and other injuries and ailments requiring surgery often meant a limited chance of recovery as with the case of Thomas McCauley in 1845 who, although ‘he was carefully attended’ died from the severity of the fractures and other injuries caused by a bullock dray accident.

Maitland Mercury, 22 February 1845

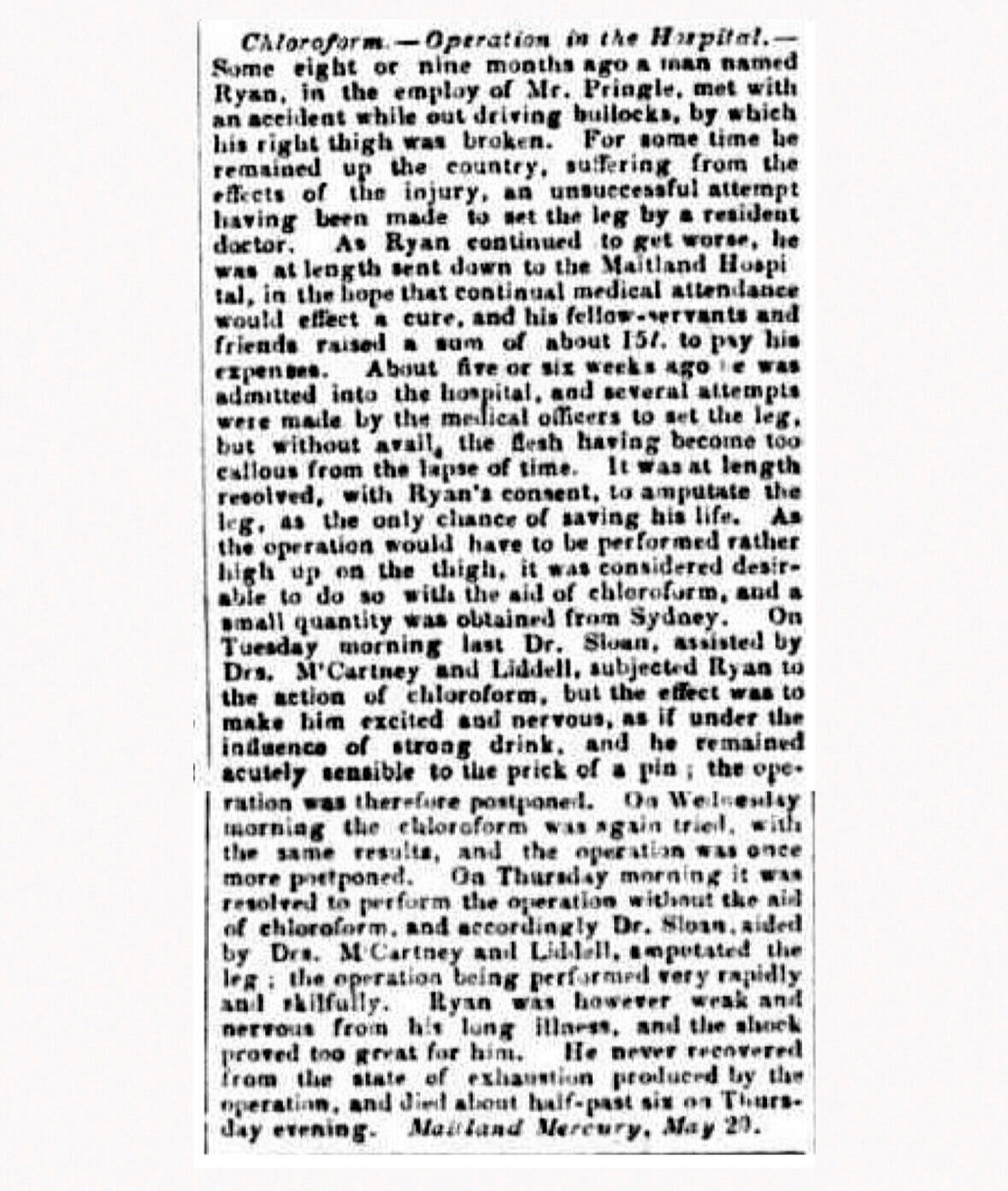

Similarly, in 1848, a Mr Ryan died as the result of a fractured thigh and despite distressing attempts to amputate his leg under chloroform.

Bells’ Life, 27 May 1848

By the 1870s, there was increasing success with surgical interventions. In October 1870, for example, Dr Morson successfully experimented with a new surgical method ‘of healing wounds by means of skin transplantation’, and on 25 February 1871, the Maitland Mercury reported on a patient’s successful recovery from ‘a very severe compound fracture of the leg’ observing that

a few years ago there would have been no chance of saving the leg of this patient, but by means of the improved resources of modern surgery the leg has been preserved, ...(though) slightly shortened.

1884 saw a peak in fever cases with thirty people admitted, five of whom died. In that year there was also an increase in the number of cases requiring operations and ‘a large number of fractures and dislocations’. The list of operations included:

1 ovariotomy, 1 amputation of thigh, 2 amputations of forearm, 5 amputations of fingers, 1 operation for piles, 1 operation for epithelioma of the lip, 1 excision of breast.

All the operations, ‘with one exception’, were reported as ‘successful’.

By 1900 the number of surgical cases had increased to 110 and, during that year, the operations included amputations; abdominal surgeries; curettage; excisions of tumours, haemorrhoids, varicose veins and eyelids; stitching of scalp wounds; and tonsillectomies. The list of medical cases covered a range of ailments with forty-five admissions for injuries, fractures and burns, and eighty-two for infectious diseases (41 influenza and 41 enteric fever). There was also an outbreak of septicaemia in the latter half of the year that prompted a thorough cleaning of the wards, and a report on the poor state of the building. Urgent surgical procedures were transferred to a building ‘detached and isolated from the main building’. Calls were made for the need for new facilities.

References and resources

A history of anaesthesia and surgery in the nineteenth century, Your World Healthcare, 2017

Joseph Lister: Surgery Transformed, 2009 (YouTube)

Maitland Mercury

Randall, Peter and Oksana A. Jackson, ‘A history of cleft lip and cleft palate surgery [epithelioma of the lip]’, Pocket Dentisty

‘Surgery’, Science Museum

The History of Surgery: A Bloody (and Painful) Timeline, Rasmussen College, (YouTube)

The Old Operating Theatre with Mark Pilkington: Medical London, 2014 (YouTube)