A grand ruckus.

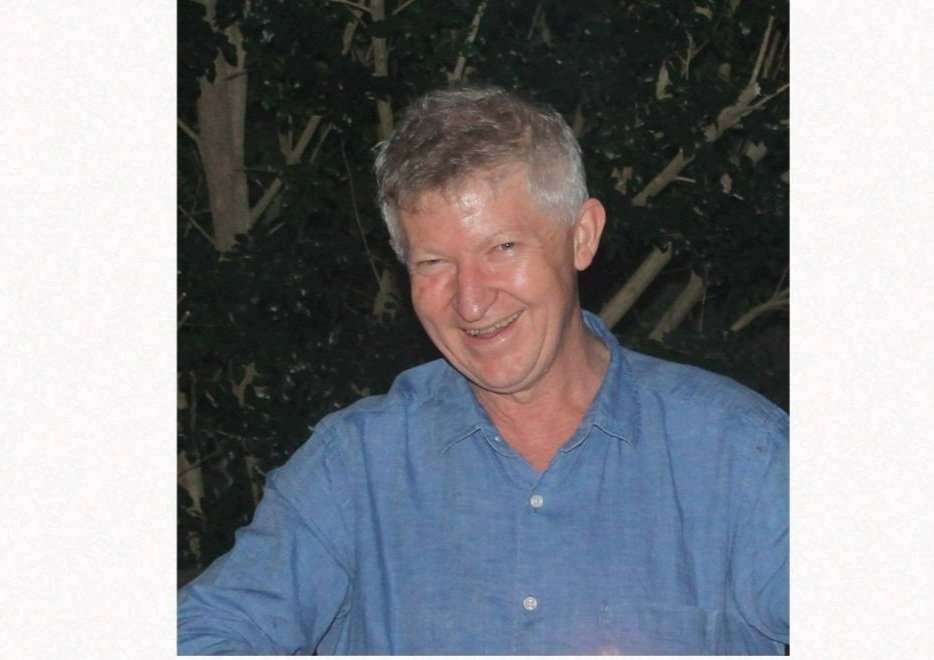

Kelvin Russell (right) is a great-great grandson of James Charles Russell who, as Kelvin explains, ‘was resident surgeon at the Maitland Hospital for a short and combative period in 1859’.

James Charles Russell and his wife are the earliest of Kelvin’s ancestors to migrate to Australia. As Kelvin observes, ‘I started genealogical research a couple of years ago to clarify some family myths (I’m not related to the Dukes of Bedford!) and have been going down rabbit holes ever since!’

One of his rabbit holes was to research and track James Charles Russell. Kelvin shares that research here.

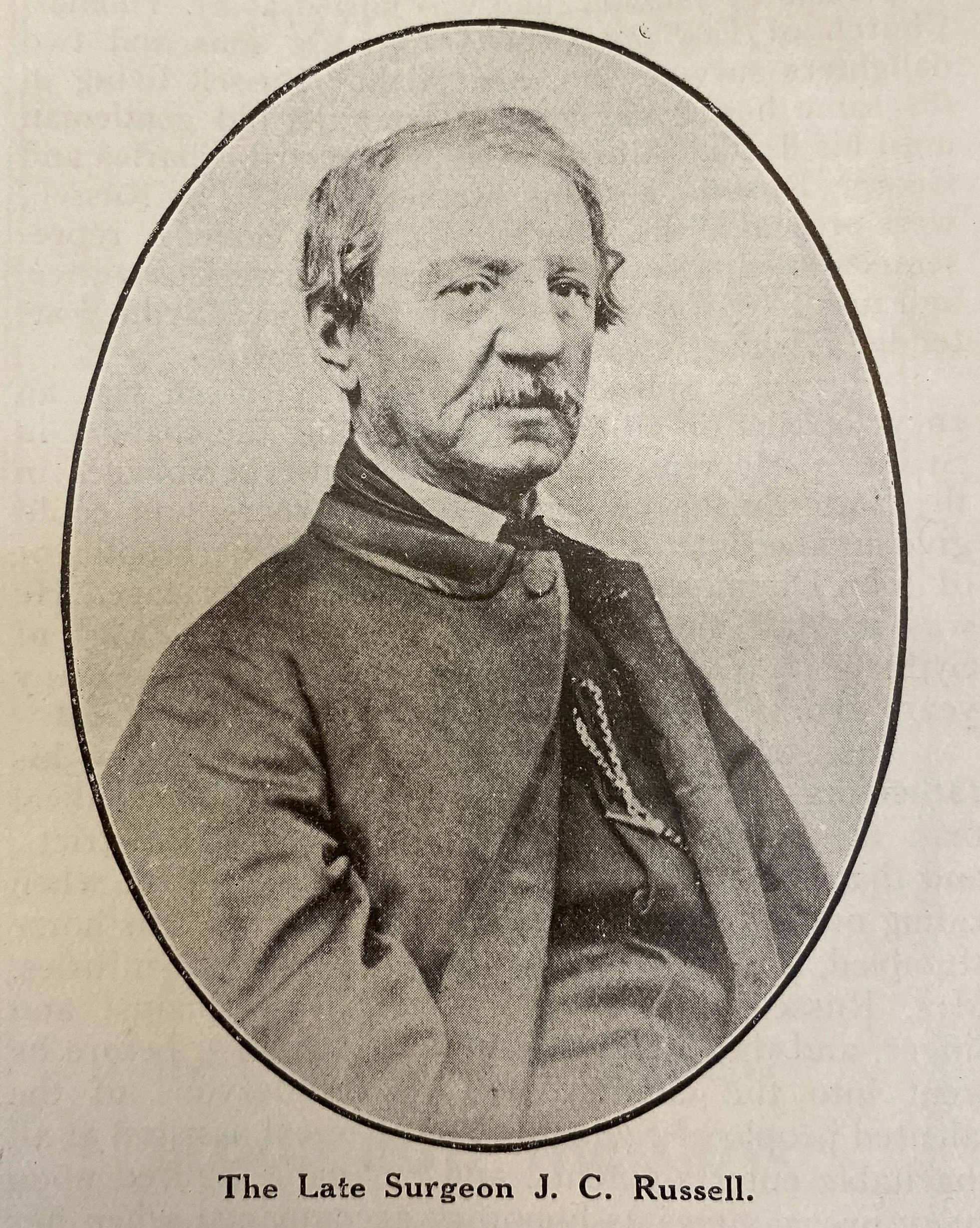

Portrait of J C Russell from Australasian Pharmaceutical Notes and News, Vol XIII, Sydney March 1, 1917, No 10, p33.

London

James Charles Russell was born in Westminster in 1805, son, grandson and great grandson of surgeons and apothecaries. He served his apprenticeship with his father and an apothecary, carrying on business with his father and eventually setting up separately. He qualified as a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1832 and adopted the title ‘Mister’, the title ‘Doctor’ being used for surgeons qualified at university.

Later that year he sailed for Van Diemen’s Land, taking a post on the Enchantress as ship’s surgeon rather than paying for his passage. On the way he met the ‘Three Misses Banfather’, daughters of a Scottish clergyman. They were relocating to Hobart to accept posts teaching with their brother who had gone there some years before and established an academy.

In March 1833, after 4 months at sea, the Enchantress arrived at Hobart. Russell took on the post of District Assistant Surgeon for the Colonial Authorities. The following year he married Maria, the middle of the three Banfather sisters.

The couple sailed to Sydney in late 1836 with their first son, Henry Denham Russell, who was 18 months old.

Sydney

Russell worked from a number of premises around Pitt Street in Sydney, practising medicine and selling drugs.

At this time the colony of New South Wales was undergoing rapid change and expansion. With the influx of immigrants came some of dubious character: not all the people claiming to practise medicine were suitably qualified. In 1838 the government publicised and then passed the Colonial Medical Act, a statute requiring that the court could only use as expert witnesses medical practitioners who were on a particular list. Although the focus of the law was narrow, only stipulating requirements for court purposes, it was a de facto list of qualified medical practitioners. This was a first in the Empire – elsewhere separate lists were held by the Colleges of Surgeons and Halls of Apothecaries.

The law was not universally appreciated because it suggested a colonial administration had authority over the English institutions that had long held the authority to determine competence. A long and colourful argument proceeded in the press of the time. All the major papers weighed in with often flowery language and quoting Shakespeare and Horace to support their arguments.

Whether because of his contempt for the law or a clerical oversight, Russell was left off the list when it was published. He joined in the exchanges in the newspapers declaring:

I shall put my diploma for seven days in the window of my shop, that every sweep in Sydney may read what I should deem a compromise of my professional rank and chartered rights.

The matter was brought to a head by Russell doing an unauthorised post mortem. Because his defence was that he was qualified under British, if not Colonial, law the case was heard by the Supreme Court of the Colony of New South Wales. The full bench found against him and fined him 50 pounds, a significant sum in 1839.

Liverpool

In 1852 the Russells were appointed Head Surgeon and Matron of the newly established Liverpool Benevolent Asylum. At this point their eldest son, born in Tasmania, started work in the Sydney Hospital as a clerk. Henry Denham Russell (1834-1917) was to remain associated with that hospital until he died, rising to the position of Secretary (CEO) and, in his declining years, being given a salary and light duties in lieu of a pension.

Maitland

In 1858 one of the doctors at Maitland Hospital used the day book to insult one of his colleagues. This breech of protocol was discussed at length in the Hospital and in the Maitland Mercury. The offending entry was crossed out, discussed further, and then excised with a knife. It caused such ill feeling that the house surgeon resigned his post. James Charles Russell was accepted as the replacement and was appointed on 23 March 1859. He remained in the position for just under one year.

Russell’s long experience in different institutions, particularly the Liverpool Benevolent Asylum, prepared him well for the requirements to both practise medicine and manage the day-to-day running of the hospital. His time at Maitland Hospital was, however, marked by tensions and criticisms.

In late 1859 the hospital’s long-standing treasurer, Isaac Gorrick, returned from a lengthy overseas trip. He complained bitterly about the ‘extravagant’ way that the hospital was being run, and that the institution that had 800 pounds in the bank when he had left had gone into debt. The implication was, at least partly, overspending on the part of Russell.

A couple of months later, Russell applied for an increase in salary, provoking a discussion in which members of the hospital spoke both for and against his request. Russell withdrew his application. The Acting Committee, however, increased its interference in the day-to-day running of the hospital, excluded Russell from the weekly meetings, and required that ‘dietary tables’ and dockets for purchases were provided each week.

Russell may well have been an abrasive character. At one stage, the cook complained and then left, incurring a ten day gaol term because of the inconvenience of his sudden departure. A nurse was insubordinate and disciplined, but later successfully complained that Russell had not cared for a patient correctly. In January 1860 he was accused by another staff member. He refused to allow the charges to be read. Instead he offered his resignation. He resigned from the hospital on 24 February 1860 but stayed to the end of March while a replacement was found.

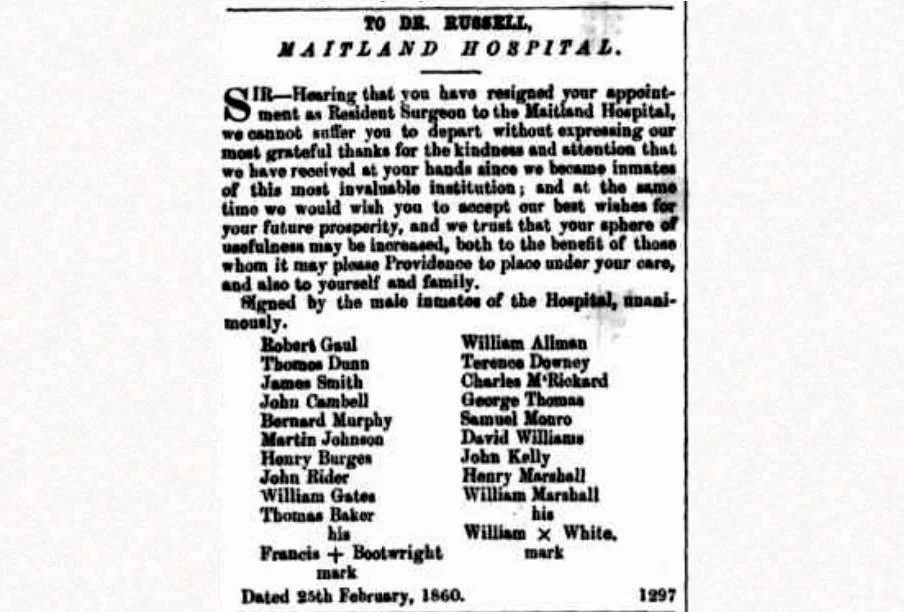

Not everyone found Russell difficult. An open letter from inmates was published in the Maitland Mercury thanking him for his care and attention:

Maitland Mercury, 28 February 1860, p 1.

Scone and Murrurundi

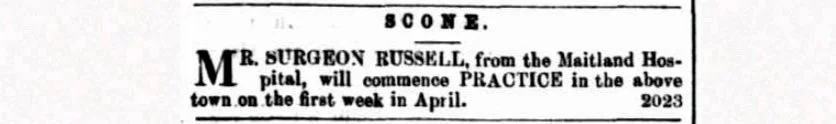

Following his departure from Maitland Hospital, Russell moved to Scone and set up a practice there. He placed a series of advertisements in the Maitland Mercury in 1860 identifying himself as ‘Mr Surgeon Russell, from the Maitland Hospital’ and that he commenced practice in Scone in the first week of April that year.

Advertisement placed in the Maitland Mercury 8 times from 31 March to 5 May 1860.

After a few years in Scone Russell moved to Murrurundi, living for a time in Bridge House which is still standing on the New England Highway. In 1865 he assisted in the formation of the Freemasons ‘Lodge of Hope’ there. He was now 60 years old. He was still practising and was also writing dispatches for the Maitland Mercury under the pen name ‘your old correspondent, Argus’.

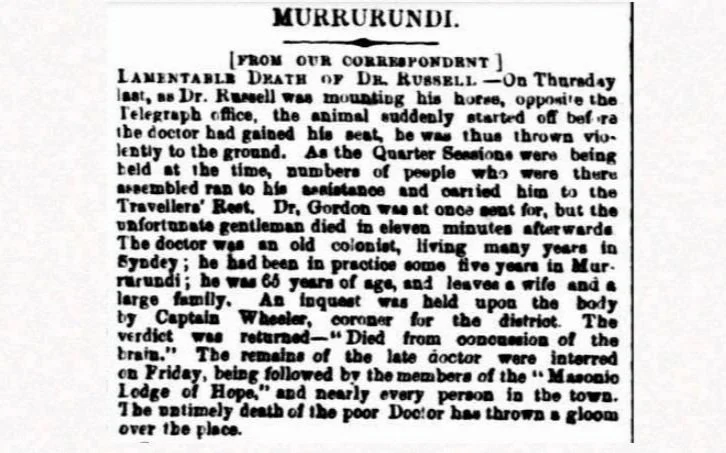

On 27 October 1867 Russell was bucked off his horse in the main street, taken to the Traveller’s Rest, and died soon after. He was attended by Dr Gordon, an ex-policeman who had turned to medicine mid-career and who was probably not on the list of qualified medical practitioners Russell had so despised.

References

‘James Charles Russell’, Australian Medical Pioneers Index (online database), last updated 17 Aug 2021.

Maitland Hospital Minute Book, 1859-1872, Old Maitland Hospital Collection, HOS2022.074.

Maitland Mercury, 21 Oct 1848; January 1859 to March 1860 passim.

‘R. v. Russell, 1839’, Decisions of the Superior Courts of New South Wales, 1788-1899, Macquarie University.

Wilton, Janis, ‘Russell, James Charles’, Views of Maitland, P603.

Posted: 8 Feb, 2022

Updated: 26 Feb, 2023